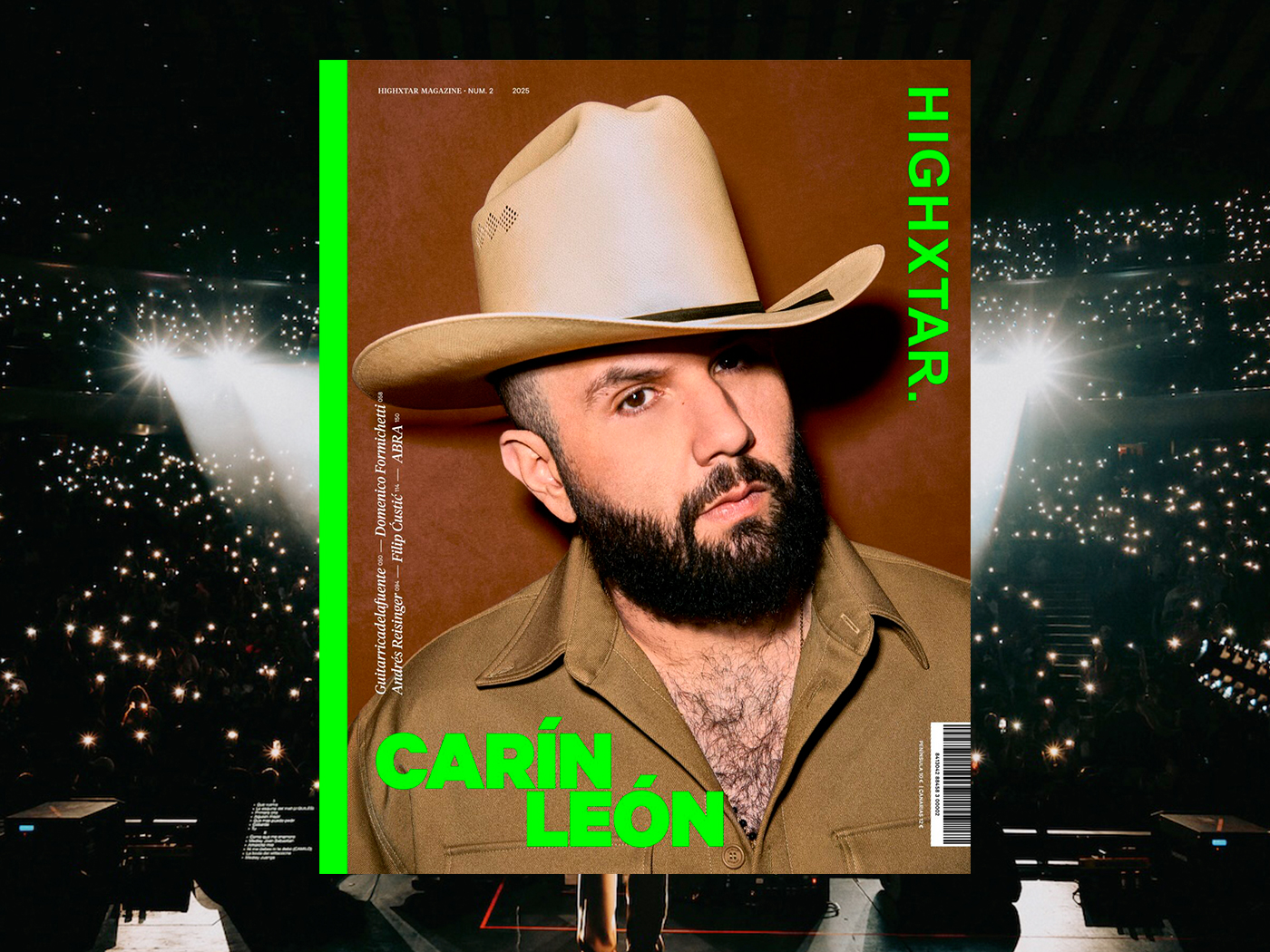

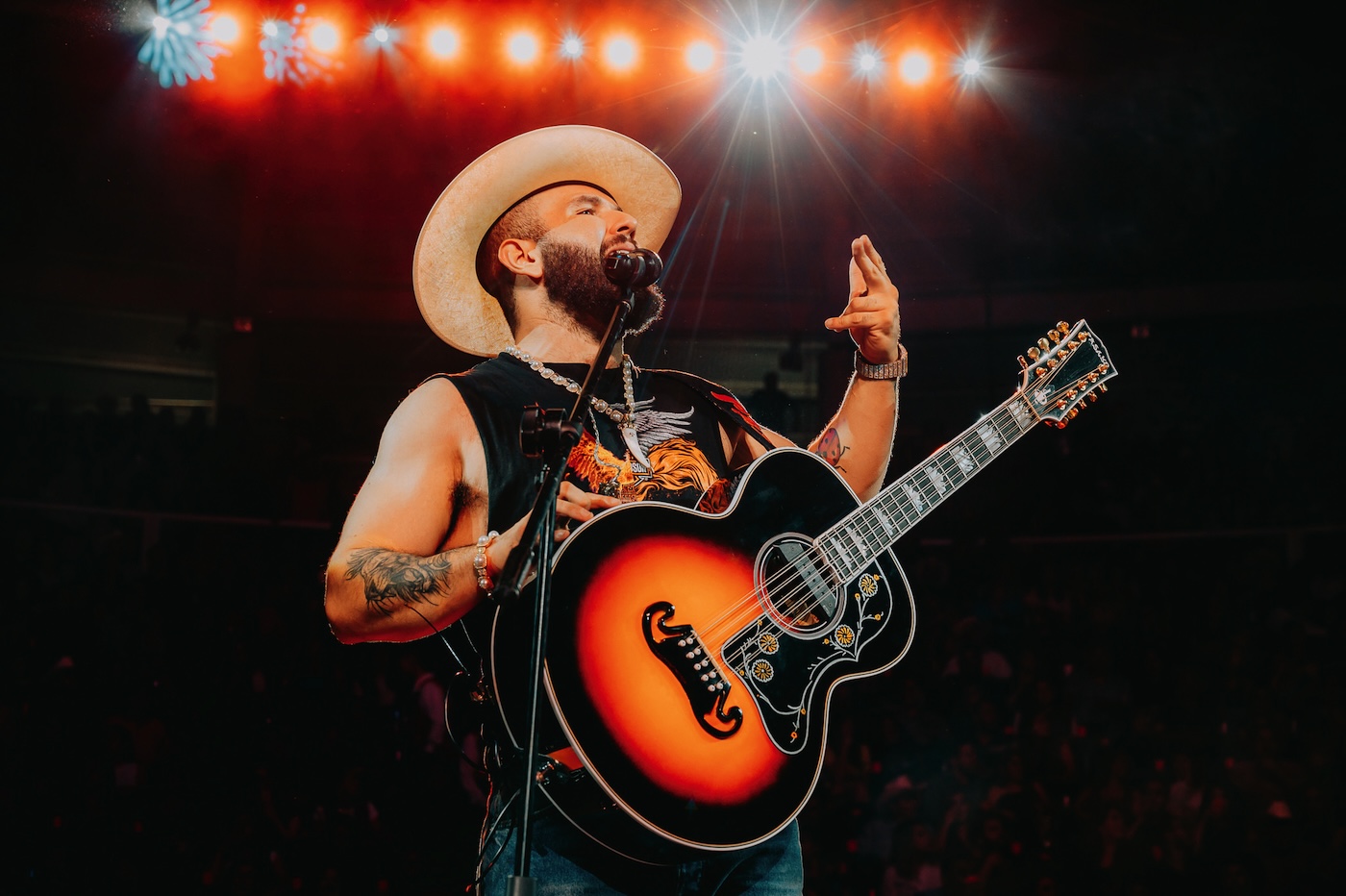

The first time Carín León (Hermosillo, Mexico, 1989) brought his music to Madrid, in November 2024, he stepped on stage feeling uncertain: “It seemed impossible to me; they say the Madrid audience is demanding—one of the hardest to win over—but once you do, they’re the most loyal.” That “advance” concert, as he likes to call it, saw the Mexican singer break the attendance record at the WiZink Center, which had previously been held by Metallica, drawing in 17,426 devoted fans.

Óscar Armando Díaz de León doesn’t let it go to his head. By now, he knows all too well that for every group of loyal fans, just as many critics are ready to fight it out on social media. “I’ve learned to embrace the haters,” he says, now at peace with the wave of memes mocking the young singer who makes odd facial expressions, like a crooked mouth (which inspired the name of his previous album). Carín León is clear that this, too, is part of who he is: “It’s my brand, and it’s not going to change just because people say so.” That’s how the singer has built a unique persona—ranchero, yet contemporary—somewhere between the nerdy kid who loved Dragon Ball and the Mexican adult shaped by telenovelas; between Quique González (whom he honors in his cover of Aunque tú no lo sepas) and traditional corridos. Proud of his roots…

HIGHXTAR (H) – Would it be fair to say you’re the Mexican C. Tangana—someone who brings tradition back and gives it a modern twist?

CARÍN LEÓN (C) – Wow, C. Tangana is one of my biggest inspirations and one of the artists I admire most. I think Tangana is in a league of his own—it would be way too bold [basado] for me to compare myself to him. I just like being seen as a crazy guy who loves music and is proud of his roots. And someone who loves to connect, of course. I’ve lived and listened through so many genres, so much music, so many artists… I try to pour a bit of all that into my own music, in a way that doesn’t feel forced. And I’m always in search of the roots—I feel like there’s a point zero from which all human music started, and I try to reach it. And I have a lot of fun doing it.

(H) – Your music reflects many recognizable roots—from the norteño style to the brass sounds of Oaxaca and Sinaloa. It all sounds distinctly Mexican, but what is Mexican music?

(C) – Trying to define what Mexican music is—that’s something even we’re still figuring out. The richness is just immense… Imagine, every 200 kilometers there’s a different way of expressing things. I try to connect it all, to link Mexican music with music from around the world—to open the door to salsa, bachata, flamenco… Music is music, and I work with the sounds that are closest to me, the ones I know best—my Mexican sounds.

(H) – Speaking of blending styles, which collaborations have been the most enriching for you?

(C) – This year, we’ve fulfilled a lot of dreams. In fact, the collaboration we did with C. Tangana (Cambia!, on El Madrileño) was something that really told me, “hey, go for it.” I think it was one of the sparks that gave me the courage to start making the kind of music I wanted to hear. The track we did with Alejandro Sanzo, or the one we just released with Cody Johnson—one of my biggest influences in country music—have been really special. And we’re also working on something new with Teddy Swims.

There’s a very important album coming soon where I collaborate with… I think we can say it now, right? We’re making a fusion album of flamenco and regional Mexican music, with artists like Niña Pastori, El Cigala, Canelita… It’s wild. And it’s all coming together with the help of some great producer friends—my compa Edu, my compa Jimbo. A lot of exciting things are happening, fulfilling dreams and taking the music in new directions.

(H) – Music has no borders, nor does it have an age. But for older listeners, there’s something that might go unnoticed by younger ones: when you listen to an album from start to finish—which is a very ‘boomer’ thing—you realize that Carín isn’t always doing so well; first, he’s super in love, then broken, then back on top again…

(C) – Wow, I guess I really am a Russian roulette of emotions—sorry, a roller coaster [laughs]. I’m either up, down, in a bad mood, or in a good mood. I think all artists have a bit of madness to keep things interesting. Besides, it’s normal for me to be working on four or five albums at the same time. So, there are so many songs that later I have to choose: what do I want to show on Boca Chueca, or what do I want to show on Palabra de Todos, because each album has its own concept, a background that’s more than just songs and music. For example, Palabra de Todos was an album focused directly on the lyrics, directly on the word. And in Boca Chueca, I wanted to invite people to embrace the things they get criticized for—embrace your demons and say, yes, I have all these flaws, but they’re also part of me.

“I’ve learned to embrace the hater”

(H) – Up and down, but also something that Mexican music has in common: lyrics as torn as a teenager’s heart; to die of love or to die of heartbreak—but to die nonetheless.

(C) – We’re very dramatic. We grow up watching novelas our whole lives, with all that drama, which we love. I think that’s part of the signature, right? It’s not just Mexican music that’s soaked in this, but South American music too—it’s our way of writing and telling stories. Take vallenato, for example, with those heartbreakingly bitter lyrics, straight from the heart.

The lyrics of your songs have a literary quality and often tell a story that isn’t revealed until the end.

I really like the cleverness in the lyrics of our genre, and the ease with which they become popular and accessible, but at the same time they tell something real. Many of the songs have a lot of poetry too; nowadays, they still keep that cleverness, that ability to say more with less. That’s what I focus on a lot: making poetry show itself in a very simple way, and being a bridge to reach more complex ideas as well. And as time goes on, we strip away a little bit of that side of Carín. The next step is in the second part of Boca Chueca, which we’ll release at the end of September, and which shows a less naïve, more developed side of Carín’s music.

(H) – Is it difficult to convince the audience of these changes in direction? How have you handled your growth as an artist—from the praise during your discovery period to the first criticisms?

(C) – At the beginning, I think any artist seeks attention. After that, I went a long time without receiving any criticism—only positive comments. But obviously, not everyone is going to like what you do. And when criticism comes, there’s a digestion period, especially with hate. Today I understand that criticism says more about the person giving it than the one being criticized. You realize there are many people throwing hate your way, but you don’t know what their life is like.

I was heavily hated for the way I sing, because I twist my mouth a lot, and memes were made about it and everything. So I said, okay, but that’s my brand, that’s who I am, and that will never change. And I learned to embrace the hater. When there’s criticism, it also means I’m doing things right, and I understood that artists need to make people a little uncomfortable in order to grow. In a way, I like provoking some questioning in people—I feel like nobody questions anything nowadays, everyone just accepts things as they are; and I try to give them things that sometimes annoy them a bit.

(H) – And how did those meme haters—who mocked your facial expressions—receive Boca Chueca?

(C) – I think it killed those criticisms. But there will always be something—there will always be a new topic, a new criticism. The key is to always be present in a genuine and honest way. This was also an important moment for my career: being on the Jimmy Fallon show when that happened, for example, was a big boost for our genre and for me. And then I release Boca Chueca and it wins so many awards: Best Regional Album of the Year, the Latin Grammy…

The best way to shut people up is by doing things. That’s why I always stay quiet but active.

Nowadays, artists go through ten thousand changes just to appear at an awards show. They lose their style, and the stylist wins. We need to return to personal branding—everyone remembers Elvis with his suit. I don’t take off my hat.

(H) – And social media? Keeping up with it can take more time than working.

(C) – Yes, there was a time when I deleted my Instagram and all that because it takes up so much time. We start forgetting about the real world and live a lot of things on social media that mess with your head, with your ears; and after a while, you think and realize that even the ideas you have aren’t really yours—they belong to other people.

That’s when I decided to let go and get back to basics. To the people around you, to question your own ideas, to rethink things. And now I don’t spend 20 minutes in the bathroom with my phone—I’m no longer wasting time. Now I use social media in a more conscious and deliberate way. So I have my moments, and I use it, but more consciously, more thoughtfully.

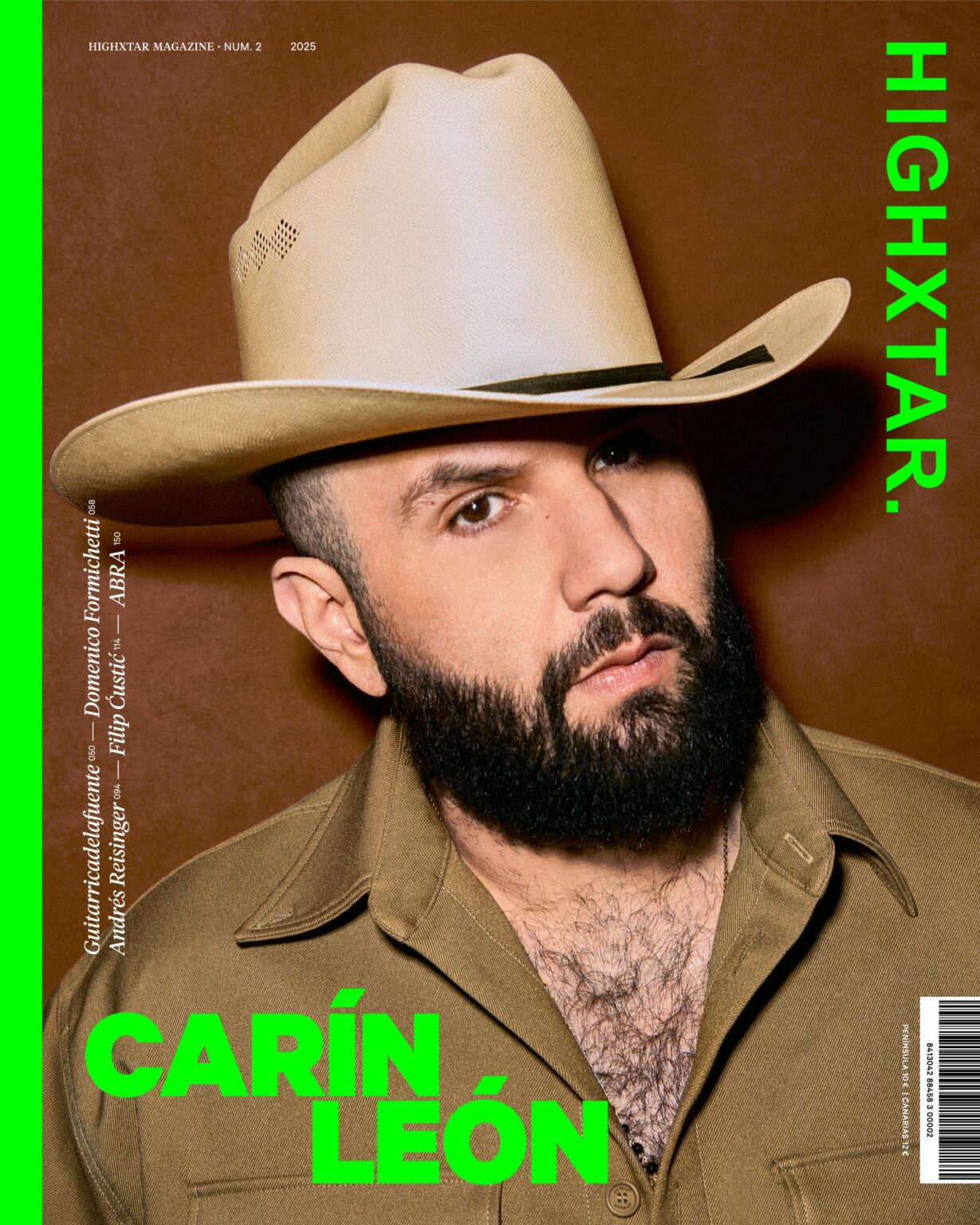

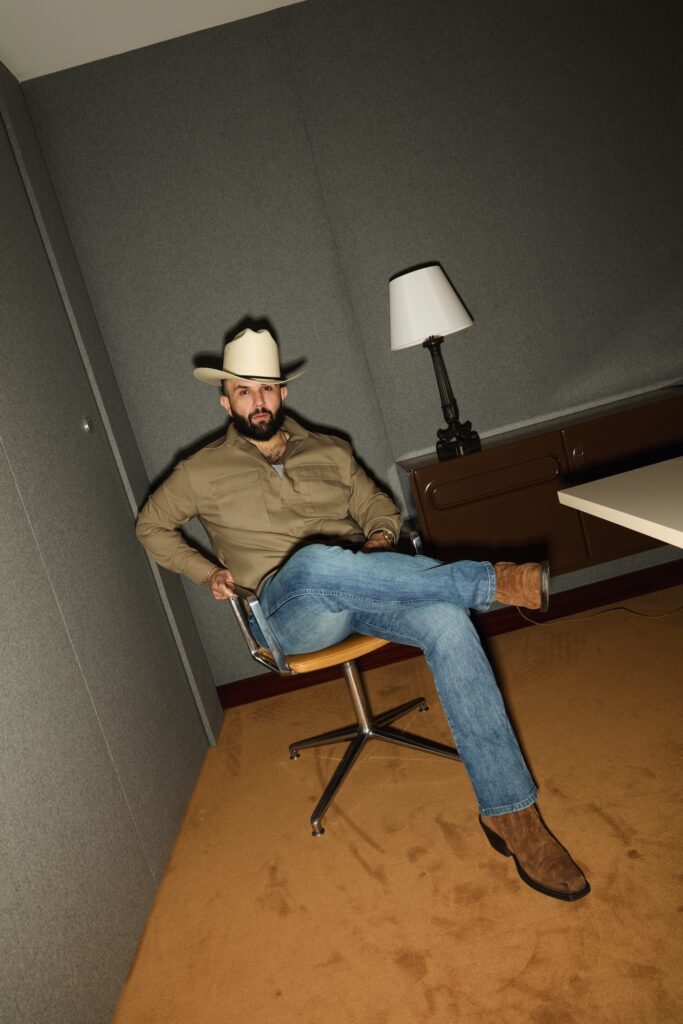

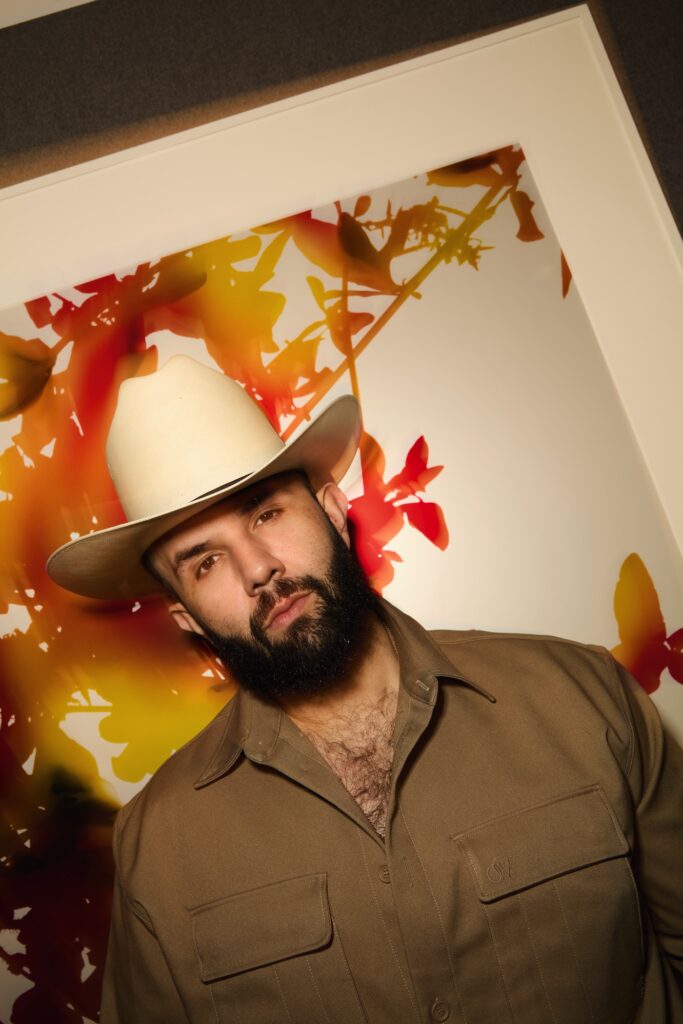

(H) – Speaking of being genuine and personal, you also have a very distinctive style when it comes to dressing—like a cowboy or ranchero.

(C) – This started with my album Inédito, which was one of my first attempts to take Mexican music toward what I liked—rock and pop influences. The clothes came hand in hand with the music. Still a bit afraid, we included a ballad on that album; but I told myself, “Let’s not get punished at dinner,” so I added it as a bonus track. Later, it became the best song on the album, and that’s when I started to realize I could be myself and make a living from this.

I also began to show myself as I really am through my clothes. I realized how important it is to have a brand, to return to a graphic identity. We all remember Elvis Presley with his suit, or Michael Jackson. And I don’t take off my hat. I think this has been lost a lot nowadays: today, the clothes are the protagonists, not the artist. We see artists changing outfits ten thousand times for an awards show. But it’s not so memorable—style gets lost and the stylist wins.

My way of dressing is what makes me feel comfortable and expresses the most about me: ranchero with a touch of rock. I like that people identify it with Carín as well. It’s not something I do intentionally—for example, the crooked hat—I wear it like that because I like it, because I can’t stand wearing a cap for more than three minutes due to my anxiety. But one day, I let the hat fall like that and I liked it, and I embraced it even more when I saw it also became a reason for criticism, about whether it’s crooked or straight… For me, it was like, okay, if you’re making people uncomfortable, you get attention.

(H) – Who are your style icons or inspirations in ranchero fashion design?

(C) – Today in Mexico, I’m a big fan of Campillo. I like how he brings Mexican fashion tradition into the mainstream. More than Mexican brands, lately I’ve also been wearing a lot of American clothes—from brands that are really working this Mexican shirt style. We see Mexican influence entering many sectors, and in clothing, there’s a strong Mexican trend as well.

But I’ve also gone to shows wearing Walmart t-shirts, which are the most comfortable [laughs].

Discover the rest of the interview in issue 2 of HIGHXTAR.

Sigue toda la información de HIGHXTAR desde Facebook, Twitter o Instagram