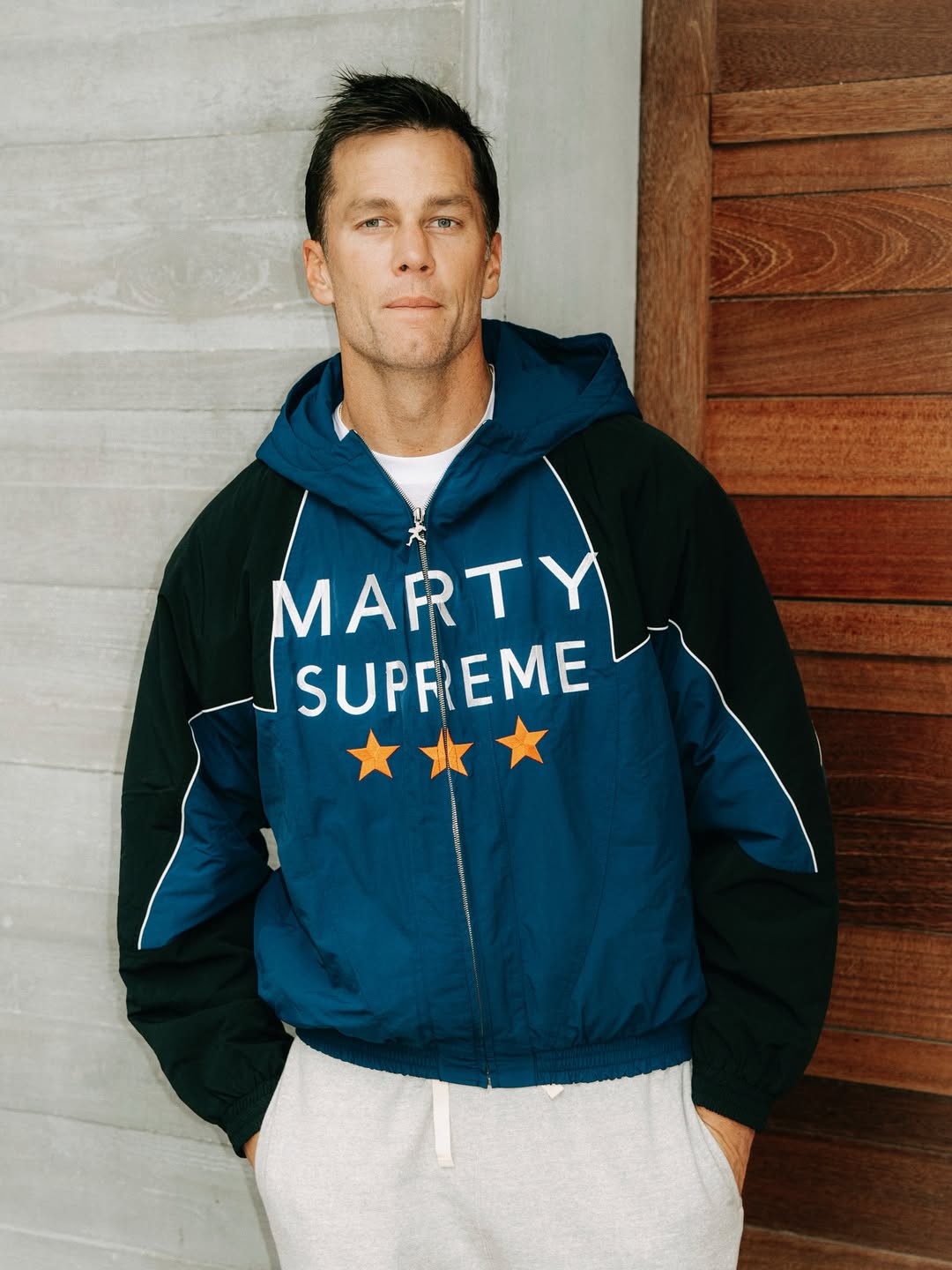

The first thing to understand about the phenomenon is that the jacket isn’t part of the film’s costume design. In fact, the wardrobe is period-accurate, fully rooted in the 1950s. That single detail changes everything: the Marty Supreme Jacket isn’t a narrative accessory but an object created for real life — conceived from the beginning to accompany Timothée Chalamet throughout the film’s press tour. And yet… it has become something far more complex, and far more global.

The jacket emerged during conversations between LA designer Doni Nahmias, Chalamet and his stylist Taylor McNeill as they tried to define how the actor should appear throughout the promotion: something that fused retro sportswear, aspirational energy, and the inherent magnetism of the protagonist. The goal was never for the jacket to “play” Marty Reisman or extend the film’s universe, but rather to capture what a sports icon can mean today.

The film, directed by Josh Safdie, follows the life of a charismatic and eccentric 1950s ping-pong player — a figure mostly unknown to contemporary audiences — allowing the narrative to explore obsession, ambition, and excellence. It’s a relatively niche story, if you think about it. But A24, the studio behind the film, didn’t wait for audiences to connect with it in theatres. They decided to build that connection in advance, out on the street. And that’s where the jacket becomes a cultural key.

The campaign takes shape when Chalamet steps into a role no actor of his generation has embodied so effectively: protagonist, creative director, strategist, ambassador, and performer all at once. The entire press tour — surreal videos with ping-pong helmets, micro-performances in Times Square, an orange blimp floating over California, and a parody video where he suggests painting monuments orange — is designed as an extension of the Marty Supreme universe. Chalamet isn’t promoting the movie; he’s living inside it. The jacket is his uniform. That’s why it works. It never reads as a product trying to sell you something, but as an object already happening before you even know where it comes from.

When Chalamet posts the exact address of a pop-up on Grand Street — just a few hours before opening — the reaction is immediate: a line of college kids, cool kids, and the merely curious stretches for blocks through SoHo, as if it were the secret drop of a cult brand. Inside, a truck filled with orange boxes and ping-pong balls acts as an accidental installation, reinforcing the universe A24 has built with surgical precision. The jackets disappear instantly — blue, red, black, orange.

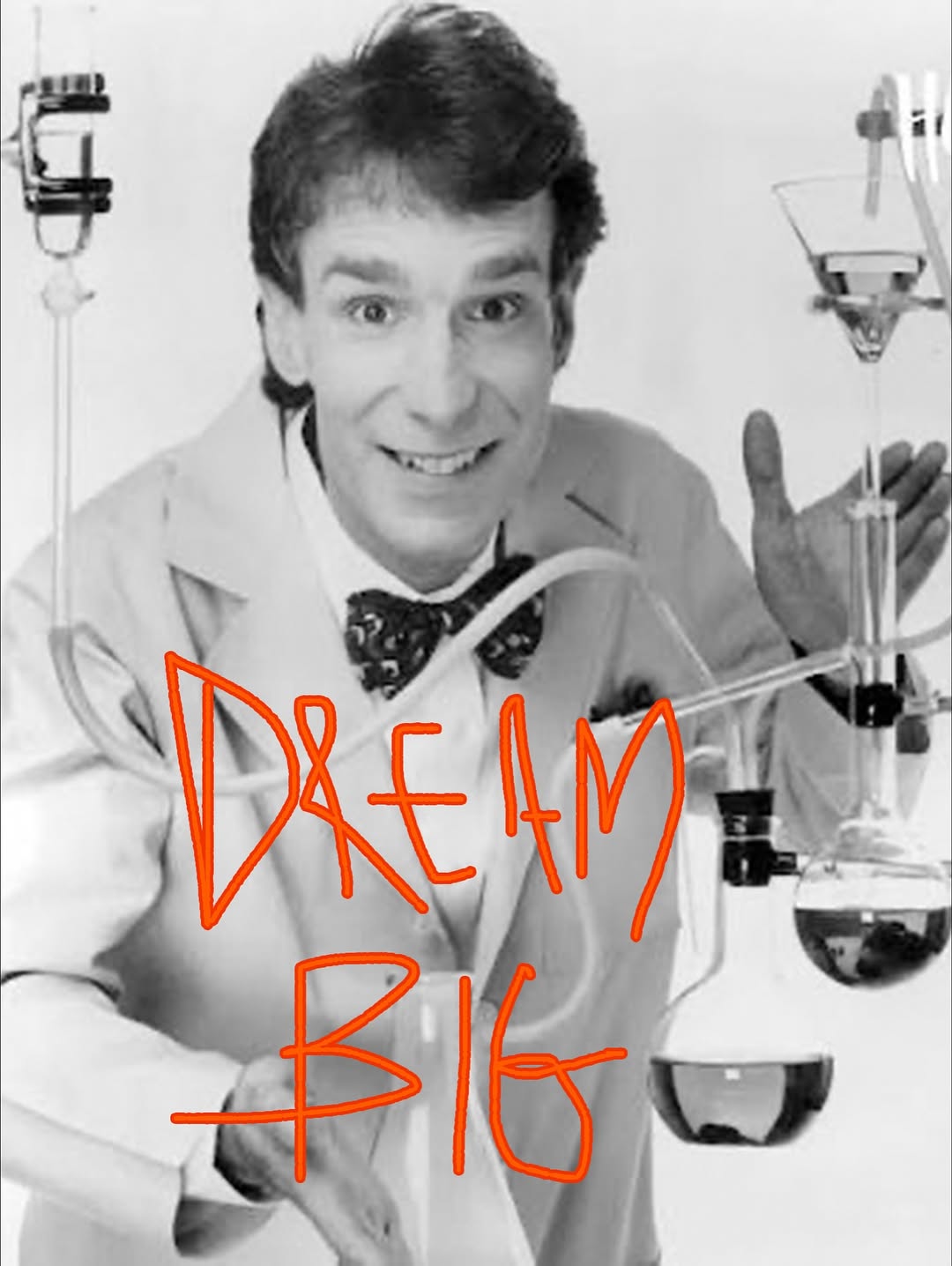

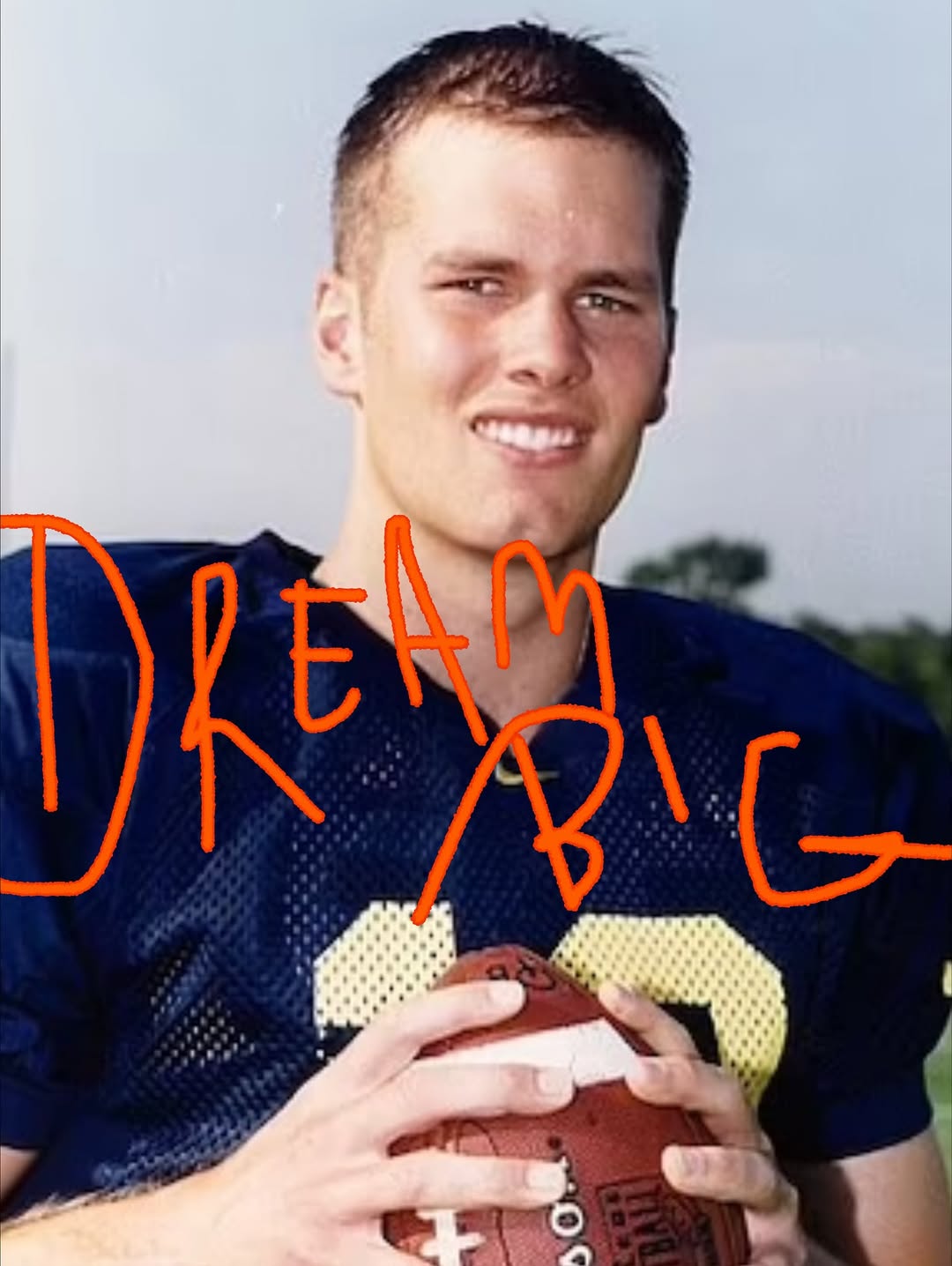

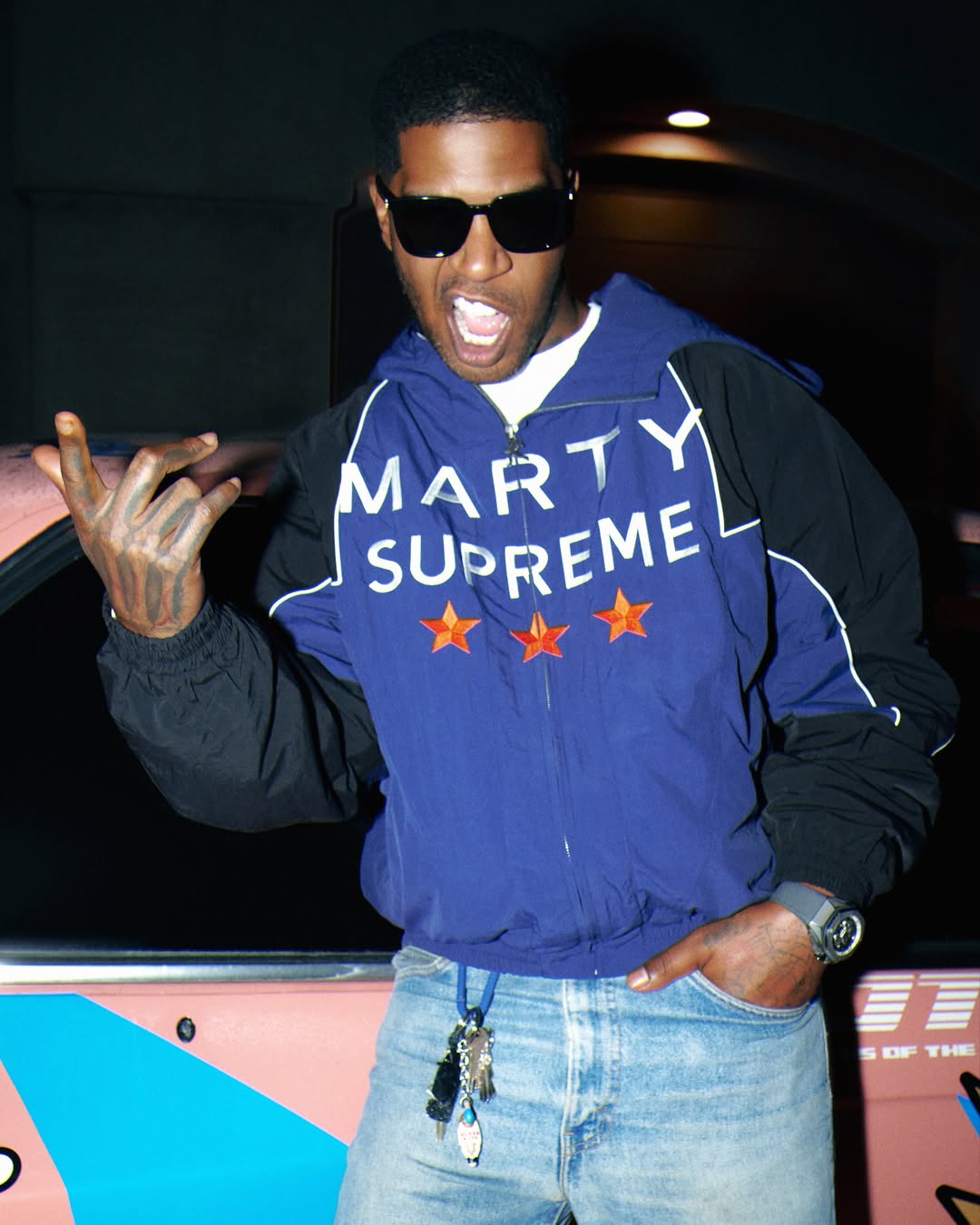

The next move is even more calculated, almost elegant in its simplicity: connecting the garment to greatness in its most recognisable form. Doni Nahmias sends one to Tom Brady; the same operation follows for Misty Copeland, Kid Cudi, Kendall and Kylie Jenner. None of them appear in the film, yet each embodies — in very different registers — the same “DREAM BIG” ethos that underpins the narrative. It’s not promotional casting; it’s a symbolic constellation. A way of building myth through a network, carefully orchestrated to feel spontaneous — but no, let’s be honest, it isn’t.

The definitive proof came when a red version resold for $4,000 on Grailed. The jacket had crossed the threshold: no longer merch, but status — cultural literacy — obsession territory. And at that point, the phenomenon no longer depends on the movie; the movie depends on the phenomenon. The most interesting — and brilliant — part is that all of this happens without the jacket appearing in the film. The fictional narrative lives in the 1950s; the aesthetic, emotional and cultural narrative lives in 2025. The Marty Supreme Jacket becomes the bridge between the two — a vector carrying the character’s energy into the present.

The jacket moves through the world, sells out, shows up on the right people, and builds a parallel narrative to the movie without any grand explanations. Maybe the charm of the whole thing is that Marty Supreme doesn’t force itself into the conversation — it slips in. It suggests itself. A jacket, a colour, an image. The rest unfolds naturally: the streets adopt it, the internet amplifies it, and the film finds its place before most people even realise it exists. A different kind of marketing conversation entirely.

Sigue toda la información de HIGHXTAR desde Facebook, Twitter o Instagram