It was not yet the 80’s and the most accurate definition of what the millennials would be, whose first members were being gestated at that time, had already been written. Eric Hoffer said: “The learned usually find themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists”. From that time until the mid-1990s, an over-trained generation would be born to deal with a world that was ceasing to exist forever. The result is the present: a constant feeling of emptiness and uncertainty. The post-modern era is marked by a serious crisis of identity that we tend to try to solve with the last path that, we believe, best respects our individualism: work.

Identity crisis

The millennial generation is desperately looking for new formulas of individual identity. And the work stands as the perfect presentation card of what we are – of what we want to be. The feeling of failure and instability is a common symptom, but the perfect mask for this is to be able to respond with a firm voice to the real question: “what do you do?”

Our working life is more geared towards meeting the aesthetic demands of the image we want to give than towards achieving a functionality that fits in with our way of life. We believe that we are looking for a job with which we can feel fulfilled, but there is much hidden behind this fallacy.

We are looking for a job that satisfies our identity desires, that speaks for us so loudly that we don’t have to be anything else, because we don’t have the strength left: I am a photographer, I am a producer, I am a designer, I am a writer, I am an artist. With which we can make up for the little we have been able to travel, the little we can pay in rent or the few hours we have from the time we leave work until we go to bed. The formula is simple: spectacularize our working life, so that we can better deal with the system’s decline in our quality of life.

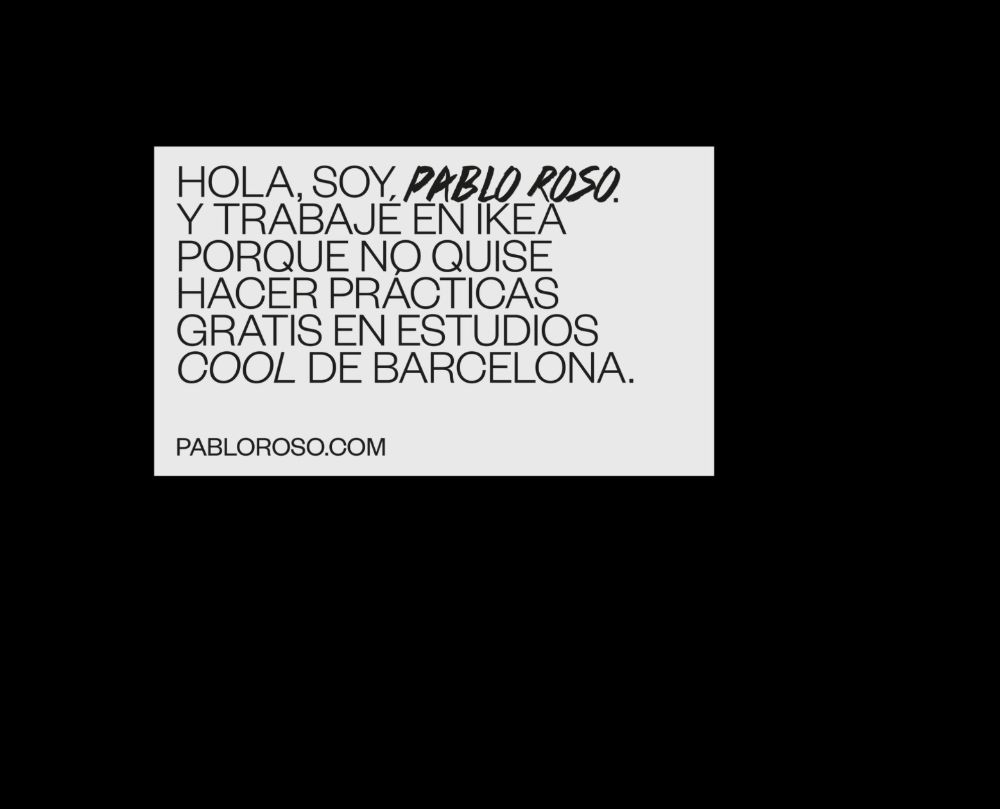

We feel a kind of relief for developing a creative work, for having a job that seems to marry passion and profession. But this reconciliation is one of the great lies of our time. Behind a façade of freshness and good vibes there is usually a well of precariousness. The millennials, so enthusiastic about belonging to the creative sphere – Remedios Zafra wrote about this – end up denigrating the rest of their lives in order to feel that they belong to a cool sector, which is nothing more than a disguised sector in order to appear attractive.

The aesthetics of modern jobs

There is a certain latent desire in big cities like Madrid – subtle and at the same time strident, like a whistle of dissimulation – to belong to the scene, to those groups of friends and not so friends that have emerged from communication agencies, magazines and other modern and precarious companies in which recognition is not in the salary, but in going out to party with the group that leads the Top 50 in Spotify. Companies that were set up years ago by some posh people and that now continue to be full of pseudo-scholarship holders in their thirties who even seem to be privileged to receive free tickets for Primavera Sound and a pair of sunglasses as a gift.

It doesn’t matter what these people do at home, because their social media feed or their description of LinkedIn is enough for them. And that is the success of our time. The failure, then, is continuing your parents’ hardware business, driving a taxi or serving some beer in a bar. We’ve even created romantic alternatives to these jobs that seemed to escape from what’s cool, from what’s worthwhile, so that we can make room for a sliver of elitism within traditional professions and small businesses. It’s not the same to be a waiter as to work in a vegan coffee shop in Lavapiés; it’s not the same to sell flowers as to have a succulent business in Etsy.

Instagram is the showcase for all of this. You don’t have to be a genius to find out who has an art studio or who works in a showroom. Because this person will make sure that it is clear in their publications. There’s nothing wrong with that, they are merely almost unconscious effects of our lack of identity. It is paradoxical, and also evident, that the search for individual identity ends up giving birth to our gregariousness.

We have ended up enclosing ourselves in fixed and static categories that we perceive as different, exclusive. It is not that you are a breaker, it is that you have friends with many followers. And there’s nothing wrong with not being one. Because not always and not in everything we have to have something new to say. The danger is in filling a trashy job with flowers or subordinating your personality to an IED title. We’re a lot more than eight hours a day trading our skills.

Fear of creative poverty

We no longer prioritize just earning more or having more free time. We feel it is crucial to enjoy a certain work status, however fragile or harmful it may be. This aspiration carries with it certain collateral damage that we somatize in insightful ways. I have little doubt, for example, that our sudden fixation on plants, orchards, dwarf goats and rural aesthetics in general has to do with a hidden desire for escapism.

Therefore, one of our greatest fears is not to be creative. This problem denotes an evident class privilege, and surely the delirium for a job in the creative sector carries an implicit dose of aporaphobia. But talking about this is indispensable to give birth to an endless number of insecurities and lack of self-esteem, among other psychological problems that pressure us. Also to try to deconstruct our system of social perception, where we relate the type of work someone performs with the emotional, cultural and personal value of that person. And that person is also ourselves. We must stop giving an esoteric conception to everything that cool leaders do and discover other threads with which to weave self-love.

Roland Barthes said it. “All of a sudden it didn’t bother me not being modern.”

Sigue toda la información de HIGHXTAR desde Facebook, Twitter o Instagram

You may also like...