I read Lolita one summer years ago. It is a book that I associate with this season without a doubt. Now, when I think of Lolita, I think of a landscape of overwhelming heat, with hints of citrus and, above all, overflowing sexuality. The dust jacket of the edition I have I suppose also helps to create this imaginary; strawberries cut in half envelop the book with a childish, playful aura. If you remove the dust jacket (which I love to do every time I buy a book); you discover a black volume, in my opinion more faithful to the narrative inside.

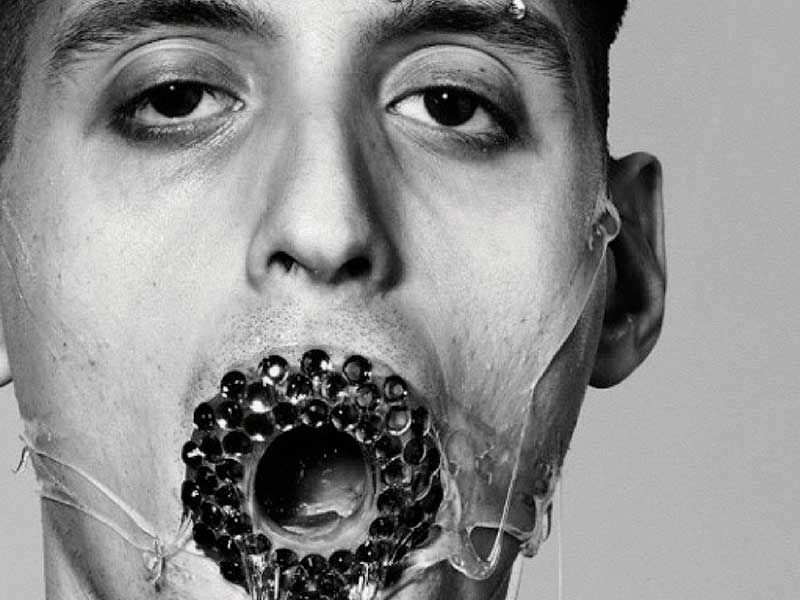

But my edition is no exception; let’s look for a second at the covers of this book: a girl with a lollipop and heart-shaped glasses looking suggestively at the camera. Childish legs, a short skirt and a long etcetera of infantilised sexuality (or sexualised childhood, I’m not sure).

Lolita is a narrative that has transcended the book, that has digressed to become an object of consumption and lifestyle. And this sets off my alarm bells, makes me ask myself over and over again: How is it possible that a story of sexual abuse of minors has been transformed into an aesthetic concept? It makes my hair stand on end every time I see an influential person displaying this ethic, an infantilised woman who at the same time has a remarkable degree of perversion. I am not saying that a woman cannot have an overflowing sexual desire; I mean that this aesthetic uses an artificial perversity of childhood that makes it difficult to see the acceptance of the sexual abuse behind it.

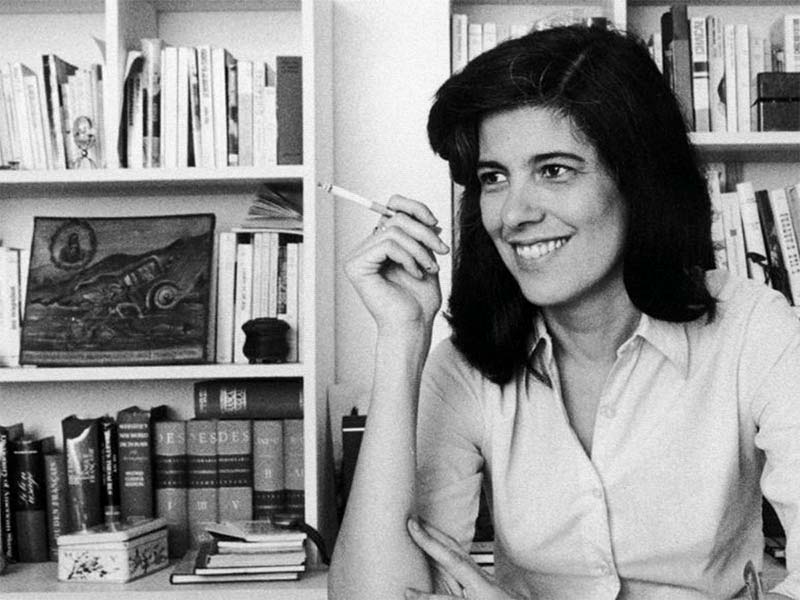

“Outside Mr. Humbert’s gaze there is no nymphet” is the phrase that Nabokov answered in 1975 to Bernard Pivot in an interview for the television programme “Apostrophes”; when the journalist asked him what it was like to be the father of a character as perverse as Lolita. Both the book and the Lolita aesthetic are stories that are usually read through the female character when there is a main component that we forget: the omnipresent gaze of the depraved. What happened with the novel is something that often happens in our everyday lives: the attempt to blame the victim for the abuse suffered; the public whitewashing of a crime.

Lolita is not a love story, as many synopses of the book suggest. How can it be possible that the relationship between a girl of barely twelve and her forty-something maths teacher (who later becomes her adoptive father) is. Maybe in ancient Greece it made some sense, but it’s long gone. Moreover, the story is told from Mr. Humbert’s perspective. At no point is the girl’s perspective known. To say that Lolita is a love story is only to pay attention to the paedophile’s version (again, very typical).

I don’t mean to knock Lolita. Its brilliance is evident. But I think the concept that has emanated from it vulgarises the book, misunderstands it and, above all, possesses a quite remarkable degree of noxiousness and danger. Let Lolita be, let us not be accomplices of Humbert Humbert.

Sigue toda la información de HIGHXTAR desde Facebook, Twitter o Instagram