Sneakers with exclusively men sizes, absence of female voices in narration, advertising by men and for men and an alarming lack of knowledge of the big names of women whose work has been key in the growth of streetwear. We analyze the panorama of this culture and business in terms of gender.

It is nothing revealing to say that we live in a men’s world. Streetwear culture and business are no exception to the rule, and if we propose to randomly throw names of the most influential in this field we will realize that we come up with many more male than female names.

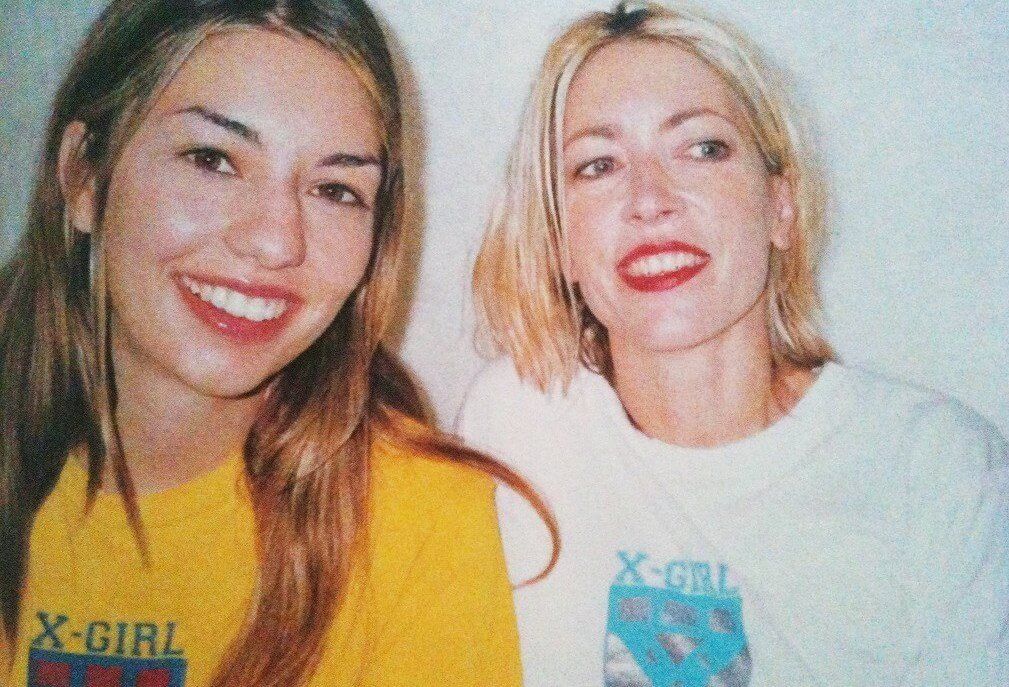

Long before it was a global industry, urban fashion was an alternative, antimainstream redoubt: a subculture in which women put some of the key pillars in aesthetic issues. Chloë Sevigny, Rosie Perez or Neneh Cherry were some of the pioneers who in the 90’s began to weave the stylistic bases of what today is a giant at world level. And without even using the word “streetwear”.

Over time, economic interests played their part, and streetwear gradually entered a much more commercial terrain until it became a big business where, as in any business project, selling was the number one objective. Urban aesthetics had to go through a series of processes to make it marketable, and in this way a key factor came into play: the public. If streetwear wanted its products to be successful in the market, it needed a global sales guarantee. And in a patriarchal society, the target always tends towards men as a standard profile.

The obstacles and traditional barriers that women always face in the business world were very determining. Little by little, business processes relegated them into a minority presence. In a world controlled by men, streetwear followed the predominant guidelines and principles to consolidate its place with high-potential business ideas and large companies.

Fortunately, these patterns seem to be changing. Companies and brands like Nike, adidas, Converse or Puma seem to have realized the opportunities that are lost by keeping women out of the game. Behaviour models, purchasing habits or the presence of elements identifiable with the feminine are some of the dynamics that present or influence women in a different way, due to identification, sociabilization and culturization issues. Aspects that are beginning to be taken into account. The road is slow and muddy, but at least we have already put the first foot.

The news seems encouraging. Various analysts venture that in the future there will be greater collaboration between men and women in the industry and that the female presence will be consolidated in all areas and departments. A greater feminist awareness and the realisation of the potential of this large sector of ignored audience have been key to setting this integration process in motion.

X-Girl or Hysteric Glamour have set historic milestones in this field. But the current general dynamic is that the people who make the crucial decisions in the big brands are never women. And their actions are barely recognized: everyone knows James Jebbia, but few can presume to have even heard the name of Mary Ann Fusco, who founded with Jebbia Union NYC. Nor will many know Pauline Takahashi, one of Stussy‘s great design leaders and creator of LA’s Funkeessentials boutique.

Much remains to be done, but the female footprint in urban culture is gradually becoming more noticeable. However, while this goal of increasing the presence of women is being achieved, the motivations for it by companies seem suspicious. Is this process driven by real feminist awareness, an interest in integrating women into the business, or is it simply a business strategy to sell more product and reach more audiences?

Sigue toda la información de HIGHXTAR desde Facebook, Twitter o Instagram