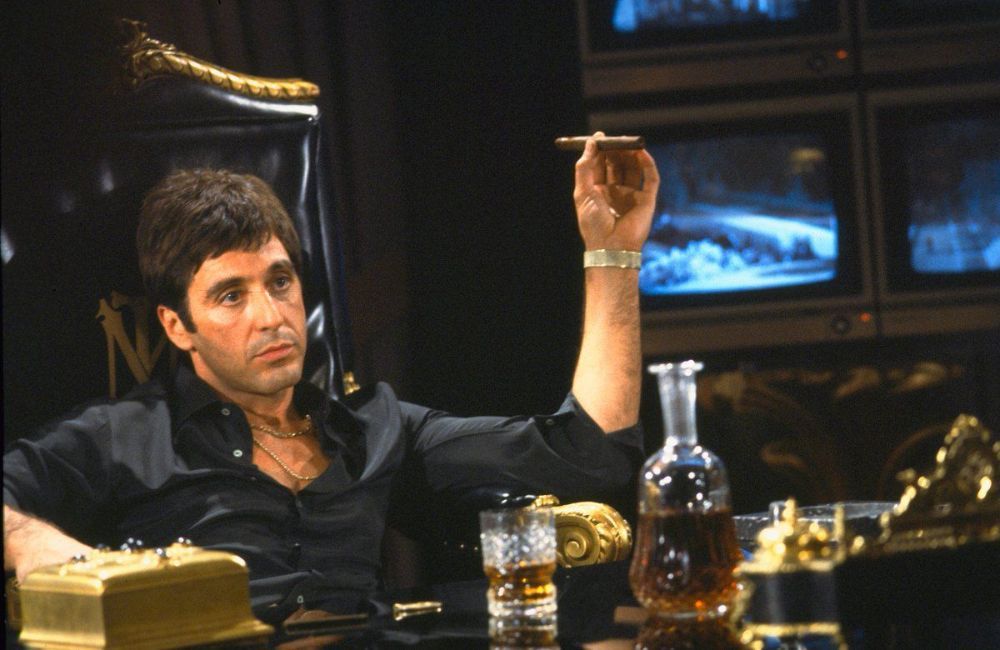

In the first half of the 20th century, the teenage idol was the rockstar. In the mid-’60s, the gangster gains ground. Since Scarface came to the big screen in 1932, the gangster aesthetic has established itself as a constant trend in fashion, with notable upturns after premieres of great narratives about the Mafia and subsequent periods of calm in which it is relegated to a minority status. We analyse how this figure was born, its current resurgence and its references.

The construction of the mafia archetype

The figure of the heroic gangster emerges as a socio-cultural effect of capitalism and its horrors. An effect that germinates in the lower classes of society and ends up being absorbed by the system, reconfigured and sweetened to our delight.

In depressed economies, the construction of one or more local criminal idols is a consequence of the search for an identity figure by the most disadvantaged. Those repudiated by the system, relegated to the lowest positions in the society of hyper-consumption and self-made man, hunger for a filiation that will calm their identity crisis.

These groups feel excluded from an economic system that prevents them from developing as people. And so they set their sights on the criminal, on the mafia man, on the one who has managed to get rich by mocking the financial network that oppressed him, by playing by his own rules. In the one who has managed to triumph within the logic of capitalism, but without subordinating himself to the system. In the one who has gone from being a passive subject to being the agent of his own life.

The writer Heriberto Yépez tells it in his book La increíble hazaña de ser mexicano (2009):

Here’s the (foolproof) recipe for making your child into a drug dealer, a criminal, someone who thirsts for more and more power.

From a very early age, it slices through his feelings, body and desires. Tell him or her that you know more about him or her than he or she does. Whatever he or she does, disqualify him or her. (Do this as systematically as you can). As you prepare a being marked by incompleteness, add machismo, classism, racism and misogyny to your taste, until your child believes that a being is complete by demeaning others. (Feeling empty is the key ingredient in this typical dish).

Once I reach puberty, your family authoritarianism increases. With emotional blackmail or overt violence. Keep a warlike atmosphere in your home. By this time, your child will seek to excel at all costs. And you and your society will certainly prevent him or her from doing so through education, love, or work. Boil it down with narcocorridos and Hollywood movies. Add two grams of coke. And bake it in marijuana or crystal. Over low heat, let it out on the streets. There you will find the nearest gang, police, cartel or army. That group – where he will find the same rewards and discomforts as in your family – will be his new family. Then he will have respect. And he will take his revenge on you and on this whole society. For dessert, play the victim and ask yourself how come there are such heartless people if you are so sweet.

Gangster and pop culture

The glorification of the figure of the mafia man is a determining factor in the constant representation of the latter in pop culture. We see him in series like The Sopranos or Breaking Bad, in films like The Godfather or The Irishman and in video games like Grand Theft Auto. Different variants of the criminal have helped to reconfigure the figure of the mafia figure of our time, a figure that starts with the old-school mafia but differs from it in several relevant factors.

The classic mafia is governed by strict rules and plays within its borders. The modern mafia has charisma and does not hide its criminal activities, but proudly displays them as a sign of empowerment. Status above ethics. And from this re-signification also arise the variants of the Latin American drug dealer or the white North American, entrepreneurial and corrupt. Archetypes who spend their money on luxury, prostitution and drugs while mocking the State. The series Narcos has led to the admiration of a certain public for the figure of Pablo Escobar. It also happened with The Wolf of Wall Street, after whose premiere many people felt ridiculously identified with Jordan Belfort.

In this way, a new market niche is generated that urges the production and consumption of a multitude of narratives around the mafia. They alter them to their liking and present them as entertainment content for the “middle” and underprivileged classes, who swallow them up and see their romanticization of the gangster imagination strengthened. An imaginary that leaves aside the real dystopian consequences of the mafia’s life and focuses on building the archetype that the public wants to see.

Fashion & mafia

The fashion system has long played with the codes and symbolisms of the mafia. We start with the Italian mafia. Good clothes, shoes and tailor-made suits made in Italy, ready to conquer America. The English dandy also had a great influence. Refined, bourgeois, accused of homosexuality, Oscar Wilde as the maximum reference. The American gangster, more strident and ostentatious, or the Japanese gangster, silent and sociopathic, deserve a mention. All these adjectives do not come from an analysis of the organized crime of these countries, but from a reading of their representation in consumer products and the mass media.

Now certain patterns have changed. Women, who are usually a mere stage or conditioner in the plot of the male chauvinist protagonist, are also beginning to appropriate an aesthetic that has always been denied to them because of what they symbolise: authoritarianism, violence, impassivity, leadership. Since Yves Saint Laurent‘s female tuxedos in the 1960s, through the yuppie aesthetic of the 1990s, women have been consolidating and reaffirming their space in these masculinized imaginaries. But even so, the lack of transversality is evident. The culture and fashion that plays with the codes of the mafia is still mainly aimed at men.

The neo-mobster

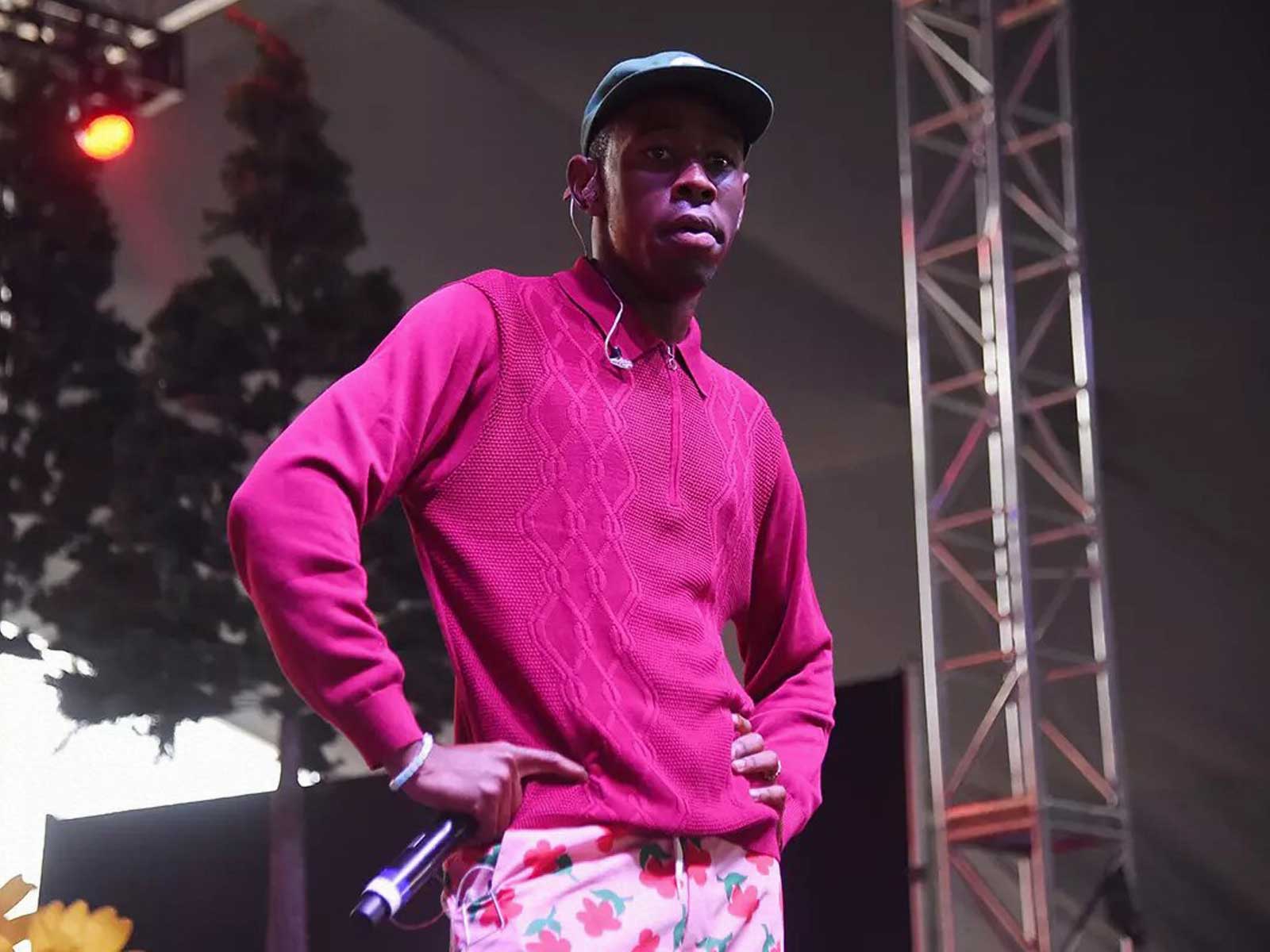

For a few years or long months now, the figure of the gangster or the mafia man has been resurfacing not only in cross-breasted suits with straps, but also in urban fashion and the most high-end streetwear. And it does so with new symbolisms and variations that it has been rescuing from other times and that it has modified and reconfigured to give rise to this new mafioso. Silk garments, watches, laces and gold seals, yellow lenses or retro tracksuits with moccasins.

We see it in the music scene, specifically in that scenario that is presented as the evolution of the trap of 2015, in that New Pop led by figures like C. Tangana (shoutout to Álex Turrión). It is a variant that drinks in part from the boom of the suburbs and shares the origin of its hunger. But that gansta wears false Gucci caps because he wants to appropriate the codes of the rich, raise and vindicate the status of the neighborhoods. The aesthetic culture of the new mobster, however, wears Margiela shoes, feels already of a wealthy class and faces institutional power from its same level, and not from below.

This whole article is not meant to tell you to stop dressing up in wide polos, silk shirts and haute couture moccasins. Rather, it is an invitation to get to know the cultural origins of your way of dressing, to know how to recognize the construction of certain archetypes and how they influence your life and, above all, to always remain analytical and awake. Because in reality this is the starting point for developing a critical view of the system: to decode the spectrum in order to become aware.

Sigue toda la información de HIGHXTAR desde Facebook, Twitter o Instagram

You may also like...